“I am always very interested in the spaces between things. And the beginnings of things. And the endings of things.”

— Sherri Rose-Walker

Sherri Rose-Walker, Poet

Story and photos by Cat Cutillo

For years, Sherri Rose-Walker has started her day in silence. She sits in her chair and looks out the window of her home on the Pacifica side of Montara Mountain.

“It’s amazing how interesting it is if you don’t turn on any devices and just start watching the world,” says Rose-Walker. “The world is amazingly interesting.”

She watches birds and insects, and often something intangible speaks to her.

“As many words as I have, I’m unable to describe what that is when that happens. There’s just something that happens somewhere,” she says. “I don’t know whether it’s in me or outside of me, and words start happening.”

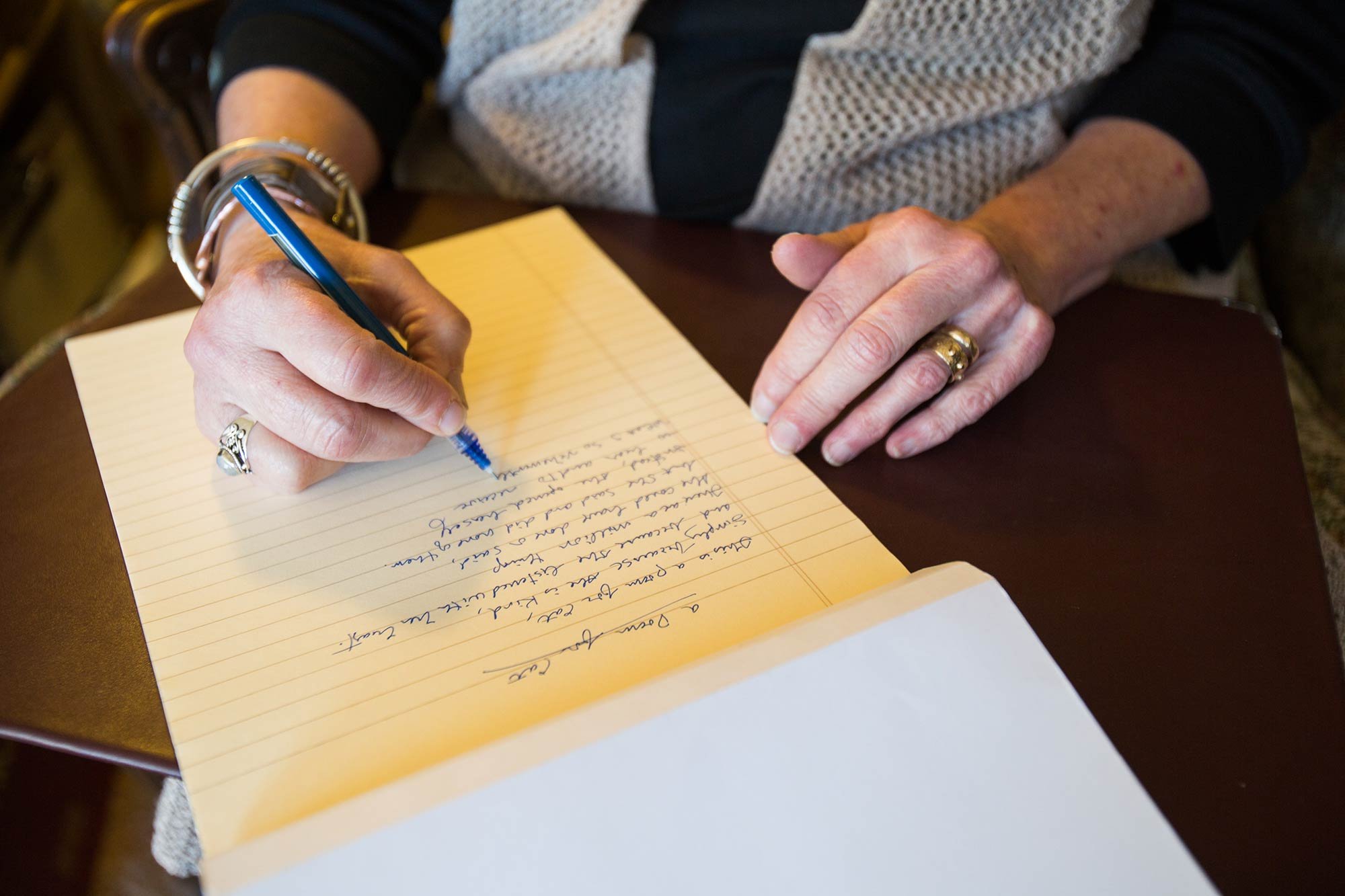

Call it what you will: A creative flow state, divine inspiration or something else, this thing that Rose-Walker can’t name has caused her to write hundreds of poems. She keeps them in different stages of completion in journals beside a chair she calls the Seat of Wisdom.

“And the wisdom is not mine. You always have to add that,” says Rose-Walker. “I tell people I’m just holding the pen. I’m just the amanuensis.”

From this chair, Rose-Walker has written an entire anthology called “Two Trees” that includes a dozen poems about the two trees that frame her view of Montara Mountain. Like bookends, these trees mirror one another, balance one another and seem to point in the direction of the beautiful view between them.

“I am always very interested in the spaces between things. And the beginnings of things. And the endings of things,” says Rose-Walker.

A lifelong voracious reader, Rose-Walker started writing poetry in her childhood, publishing her first poem in the newspaper at age 7. Mostly her poems went unread, tucked away in a journal that no one but her ever opened, until finally her writing tapered off and stopped altogether.

And no one might have ever known the jewels Rose-Walker could weave with words had it not been for a tragedy in her family. Her brother had lost a 1-day-old child, and suddenly Rose-Walker needed to write a poem. The grief reignited her poetic flame, except this time she had an audience of one—husband Bob Walker.

Her husband became an integral part of her poetic process. He would take her to a miniature amphitheater within a miniature redwood grove in the botanical gardens behind the football stadium at the University of California, Berkeley. He would sit in the stands and Rose-Walker would stand on the stage and read all her new poetry to him.

“And what he told me was, ‘Poetry is not really alive until its given breath,’” says Rose-Walker. “The breath is holy. It’s the breath that gives life.”

Now, three decades later, Rose-Walker has more than taken that theory to heart. She is entering her sixth season of running a poetry open mic series at Florey’s Book Co. in Pacifica. Poetry at Florey’s is something she and her husband began together.

“It’s the greatest gift you can give anybody. Stand up there and tell me something that you want to tell me, that means something to you. I’m here. I want to listen. I want to hear you,” says Rose-Walker. “There is nothing more valuable than that—child or adult. I don’t care who it is.”

Expect any number of unexpected treasures at any night of Poetry at Florey’s. Like the unknown couple who came in, the man fresh out of jail who got up on stage and said he’d written this poem the day he was given his sentence and realized what was going to happen to him.

“And then he read this poem that was so powerful and so heartbreaking,” says Rose-Walker. “We were all crying.”

Or the time the young girl came in with her mother to read a poem at open mic that she’d written for a school assignment about her sister.

“This poem just knocked everybody’s socks off. We loved it and we loved her,” says Rose-Walker, remembering a standing ovation.

“It was just the kind of thing that you want to have happen. That somebody could feel that they could do this at this place. That’s the upside of being a little homespun venue, that people are not going to get scared by it,” she said.

The aesthetics have also been important to Rose-Walker, who brings food, drinks, tablecloths and flowers, and organizes two featured poets to read before open mic begins. She and her husband worked like bookends at the event; she manages the front of the room and he manned the back, holding the event together.

“We would sort of divide and conquer,” says Rose-Walker. “And it became very clear that he’s in the back and I’m in the front, but this energy is converging.”

That poetic dance between Rose-Walker and her husband can’t help but remind you of the two trees. But the view from Rose-Walker’s chair has changed. The space between the trees has grown in over the years. In August came the shocking news that Bob Walker had terminal cancer.

Before his death, he completed an anthology of Rose-Walker’s writing called “Celtic Ray.” He chose an interwoven circular graphic for the cover. The poems are bound by what Rose-Walker calls an ancient Celt perspective.

“Like their interlaced design, their paths are twining around and always lead back to the center. That is probably the single most important idea about what their life perspective was—that everything, in other words, is connected,” she says.

Rose-Walker now wears a new necklace that resembles the graphic on the cover of her “Celtic Ray” anthology.

“I bought this this year as a gift for Bob to give to me because, if he had seen it, he would have bought it for me,” she says.

Rose-Walker has given herself another gift, too. She will continue on with the poetry series at Florey’s Book Co. and to keep breathing poems to life—now, with a much bigger audience.

“To me, the poetry reading is an endangered species. It’s an ephemerally beautiful thing. And it’s the reason I finally decided I would go on with my series even though Bob has died. Because poetry is about the heart,” says Rose-Walker. “We all need to be able to share our hearts.”

Against the Tide: Sherri Rose-Walker